The Jewish Museum in Berlin, Germany by Daniel Libeskind

The Jewish Museum in Berlin might be one of the most important buildings in Daniel Libeskind’s career. The Polish-American architect was born to holocaust-survivor parents (on May 12, 1946) and in his own words it influenced his design: “It’s important not to repress the trauma, it’s important to express it and sometimes the building is not something comforting. Why should it be comforting? You know, we shouldn’t be comfortable in this world. But seeing what’s going around.” Winning the commission of the Jewish Museum in Berlin in 1989 initiated the founding of his own architectural firm in Berlin, Libeskind Design. He later moved his firm to New York after winning the competition for the “Master Plan of Ground Zero” in 2003.

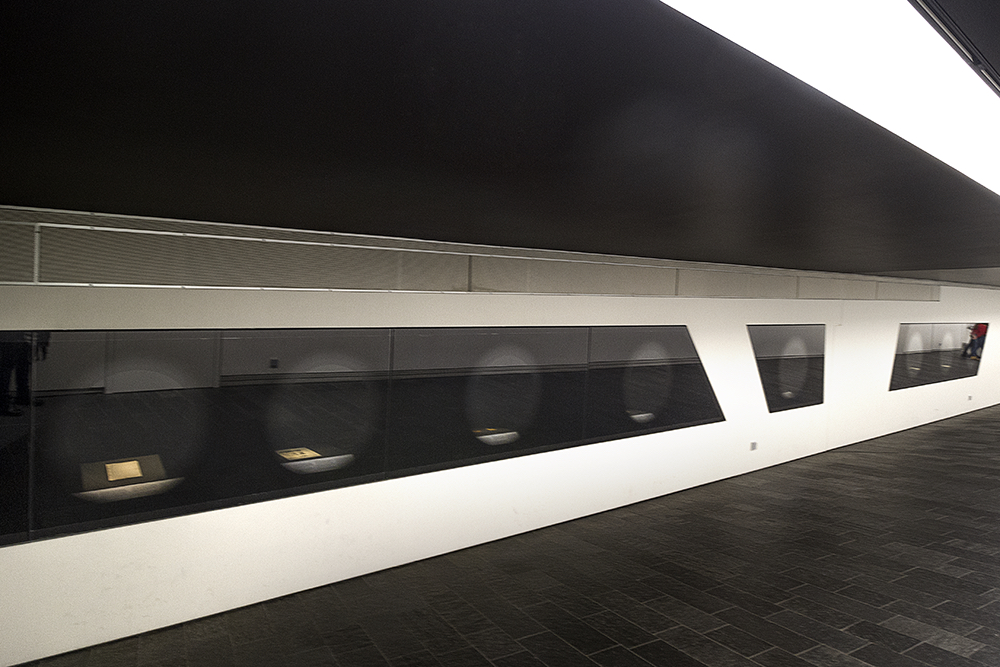

After a decade long construction period, the new Jewish Museum opened first as a bare building in 1999 and attracted in its first two years 350,000 visitors. The permanent exhibition was installed in 2001. Libeskind calls his design “Between the Lines”, and it clearly carries his signature elements of angular forms, diagonally sliced windows, and intersecting planes. The new building stands separately beside the original Baroque Kollegienhaus and is not equipped with any entrance or exit but is only accessible by a connecting underpass. Libeskind’s 166,840 sq. ft. building is laid out in a zigzag pattern, creating three distinguished axes, that have monumental importance according to the museum: “Three axes cross on the lower level of the Libeskind building, symbolizing three historical developments of Jewish life in Germany: the Axis of Exile, the Axis of the Holocaust, and the Axis of Continuity.”

Daniel Libeskind’s design has won several prestigious architectural prizes and praise such as by Evan Parka in the Arch Daily: “Libeskind’s Jewish Museum is an emotional journey through history. The architecture and the experience are a true testament to Daniel Libeskind’s ability to translate human experience into an architectural composition.”

But Libeskind’s design also earned harsh criticism such as by Edward Rotsein in the New York Times: “The building, for example, proposes that the shattered, fractured world of the Holocaust is best suggested by shattered, fractured space. You enter the exhibition by descending a lobby staircase that leads into a world of skewed geometry. The floors are raked and tilted. Displays are off-kilter. And rather than feeling something profound, you almost expect moving platforms and leaping ghosts, as in an amusement park’s house of horrors.”

It might be up to the visitor to decide if Libeskind’s approach has achieved what he set out to do. Libeskind noted in a statement about his approach: “The new design was based on three conceptions that formed the museum’s foundation. First, the impossibility of understanding the history of Berlin without understanding the enormous intellectual, economic, and cultural contribution made by the Jewish citizens of Berlin. Second, the necessity to integrate physically and spiritually the meaning of the Holocaust into the consciousness and memory of the city of Berlin. Third, that only through the acknowledgment and incorporation of this erasure and void of Jewish life in Berlin can the history of Berlin and Europe have a human future.”